Picolarium and Polarium passwords

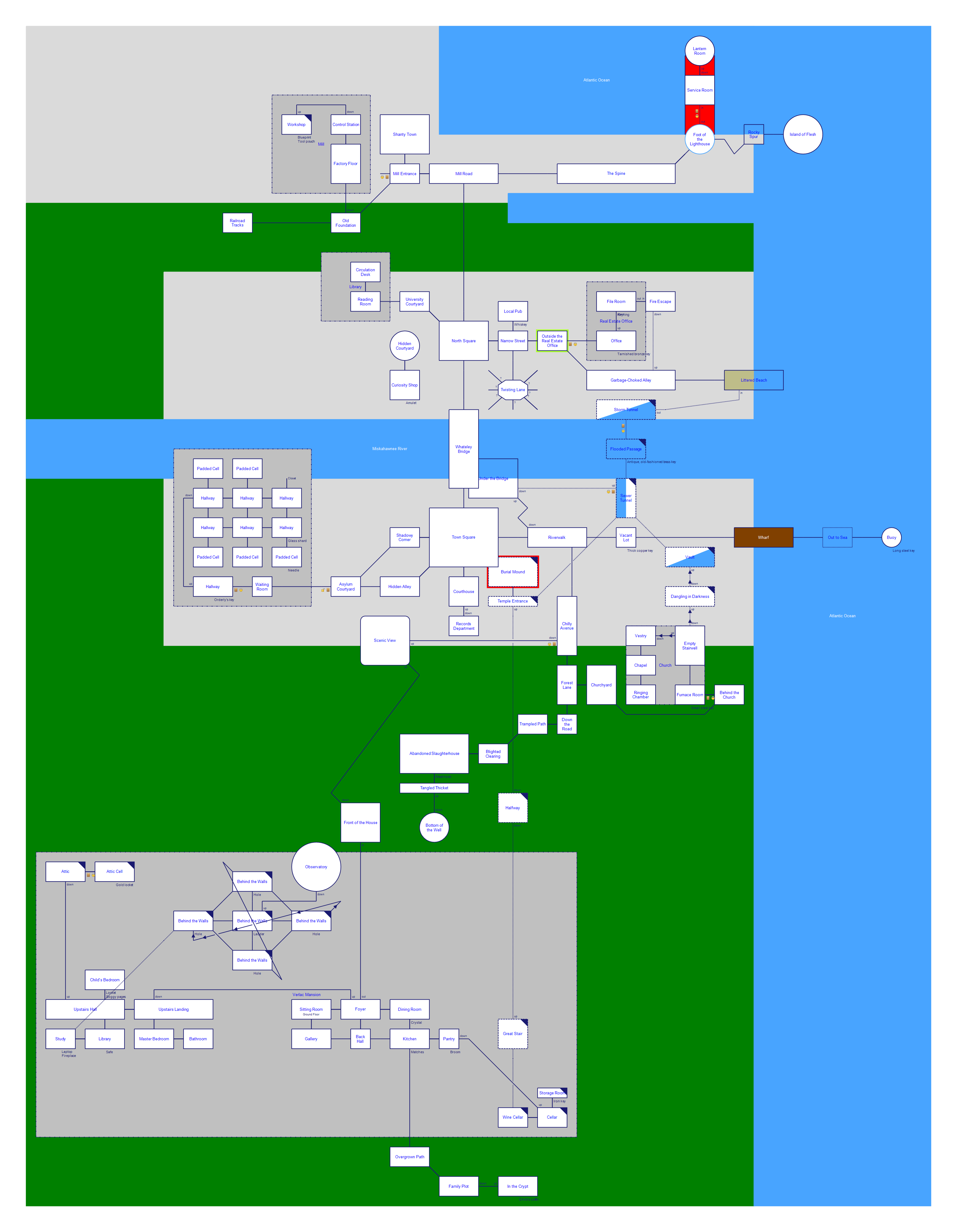

A few months ago, I published my first game Picolarium, a “demake” of one of my favorite puzzle games, Polarium, made in PICO-8. You can play Picolarium here.

I just updated Picolarium with some new features:

- Picolarium now has a level editor! You can create levels, export them as passwords to share with others, and import other people’s Polarium/Picolarium passwords to play their puzzles. Feel free to share puzzles as comments on the game page.

- If you’re stuck on a puzzle, you can now get a hint. Just press ENTER or P to bring up the pause menu, and then “Show hint”. There’s no penalty for needing help!

I decided to do a little write-up on what I had to do to accomodate for this, since it involves a little deep dive into the Polarium password system.

Behind the scenes

When I first published Picolarium in May, it was just a small clone of the 2005 Nintendo DS game Polarium – you could play the game’s 100 levels, but that was it. What I really liked about Polarium back in the day, though, was the ability to create custom puzzles and share them with others. There was a pretty large online community back then that shared puzzles with each other, using the game’s password system. Supporting those passwords would be cool.

Picolarium is a PICO-8 game. PICO-8 is a “fantasy console”, with some strict limitations to make it feel like the early generation video game consoles (and to foster creativity). Those limitations are stuff like: A fixed 16-color palette, 8x8 sprites, a 32 kb “ROM”, and a limit of 8192 “tokens”. A token is basically a part of the code, like a Lua keyword.

Level representation

When I first made Picolarium, its 100 levels were just stored in the code as tables. A level is just an 8x8 (or smaller) grid where each cell is one of two values: A black or white tile. If the level was 8x8 with alternating black and white tiles, I stored it as a two-dimensional table like so:

{

{1,0,1,0,1,0,1,0},

{0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1},

{1,0,1,0,1,0,1,0},

{0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1},

{1,0,1,0,1,0,1,0},

{0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1},

{1,0,1,0,1,0,1,0},

{0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1}

}

That clocks in at 73 tokens. Each table element is one token. Not all 100 levels were 8x8, but it added up.

I didn’t really see any reason to change the format when I started. It was easy to parse, and I didn’t really think I needed to add anything to this basic game. As you see, I even used numbers for tiles too, instead of booleans. Numbers in PICO-8 are 32-bit, so this was pretty memory inefficient. I actually do Game Boy homebrew too, where I would’ve been crazy to do anything like this, but why not do it the fast and fun way here?

When I decided to add a level editor, I needed to make room for it. I had to store the levels in a more token efficient way.

Polarium passwords

I really wanted to support Polarium’s password system too, where you can export and import 30-digit passwords to share custom levels with each other. Otherwise, there really wouldn’t be any point in having a level editor. So why not just store the levels internally as Polarium passwords?

Googling around, I found a blog post by Johnathan Roatch that explains Polarium’s password algorithm. I’ll sum it up here. To encode a level as a password:

- Convert each row of the puzzle to a binary byte (8 bits): A black tile is 1, a white tile is 0.

- If a line is shorter than 8 tiles, pad it (with anything) at the end so it’s 8 bits.

- If there are fewer than 8 rows, add bytes (they can be anything) at the end so there are 8 in total.

- Put together four and four bytes, so you have two 32-bit numbers that represent the board in binary.

- Reverse the bits of each 32-bit number.

- Now create a third 32-bit number with this metadata about the level:

- Size: The height of the level, in 4 bits

- Size: The width of the level, in 4 bits

- Hint: The Y coordinate of the starting position, in 4 bits (0 and 9 are the border tiles)

- Hint: The X coordinate of the starting position, in 4 bits

- Hint: The Y coordinate of the ending position, in 4 bits

- Hint: The X coordinate of the ending position, in 4 bits

- Checksum: Add all bytes you have so far together (that’s 4+4+3 bytes, 11 in total). Put the last byte of the result in front of the other metadata bytes.

- Now reverse the decimal digits of each 32-bit number. You have a password!

I said earlier that PICO-8’s numbers are 32-bit, so that sounds like a perfect fit, right? Not so fast. PICO-8’s numbers are actually 16.16-bit fixed point, which means that they can’t represent 10-digit long decimal numbers natively, just numbers with up to 5 digits before the decimal point and 5 digits after.

That doesn’t matter for storing the 100 stock levels though. So I just stored them like three 32-bit values internally. The example level from before would be stored like this:

{

0b1010101001010101.1010101001010101,

0b1010101001010101.1010101001010101,

0x0088.1188

}

I represent the tile data as binary, so I can easily read the black and white tiles, but the metadata makes more sense in hexadecimal. I didn’t bother calculating and putting in the checksum.

That’s 4 tokens. So I just saved myself 69 tokens. The function to decode a level, by just doing the reverse of the above algorithm, is 189 tokens, and I’m (clearly) not good at optimizing for tokens, so it could probably be shorter. Anyway, I saved myself lots of tokens here. Enough room for a level editor!

Level editor and password encoding/decoding

OK, so I made the level editor. The details of that aren’t very interesting, but I did have to change a lot of my code around to accomodate for it, and to be able to reuse the stuff I’d already made. The level select screen, for example, was hardcoded to the 100 stock levels; I changed it so it can also display the 20 custom levels (in fact, the level select screen is represented as a level behind the scenes too, just a special one with no border!).

After you’ve created a level, and solved it to both prove it’s solvable (so we don’t generate passwords that are invalid and not supported by Polarium) and also to provide the starting and ending hints for the metadata, we save it in the same format as the stock puzzles. Each PICO-8 “cartridge” (game) has 256 bytes of savedata (another one of those limitations that emulate old consoles), which makes room for 20 custom puzzles (12 bytes, remember) on top of the saved progress on the stock levels (100 bits = 12.5 bytes).

Now I needed to encode this level as a password and display it, though. That meant I actually needed to be able to represent each 16.16-bit fixed point number as a 32-bit number. I didn’t need to for the stock puzzles, but I did now. So I cheated and asked the ever-helpful PICO-8 community for help.

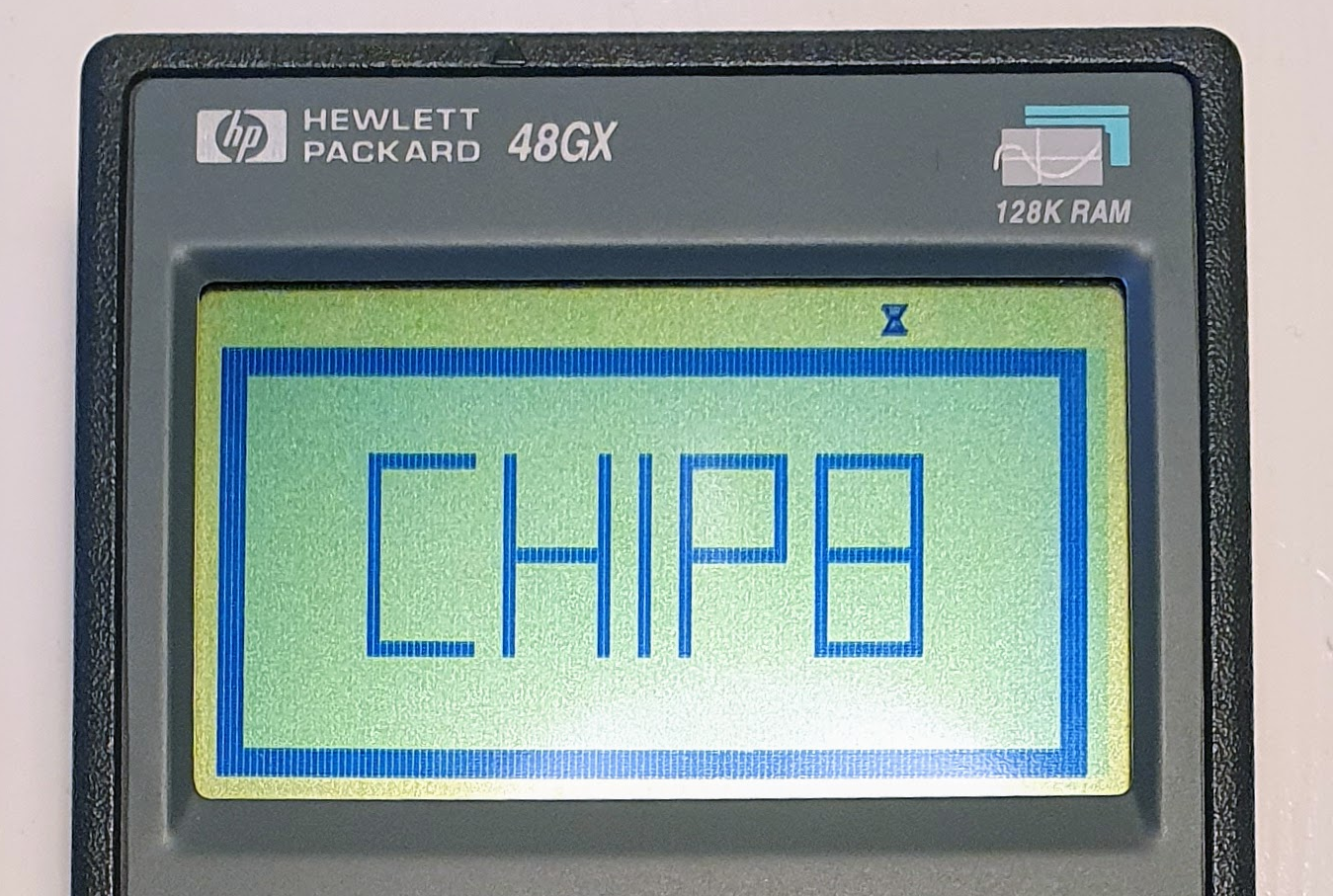

A little bit flipping later: Success! The level editor could now save levels and export them as Polarium passwords. To support importing passwords I had to make a screen with a number pad to input a password. That was a little involved, but worked fine. I also found out that PICO-8 games (which actually just support a “fantasy controller” with four arrow keys and two buttons called O and X) can activate “devkit mode” which allows full keyboard input support, which makes inputting passwords much easier.

I ran into an undocumented feature, though: The 8 key on the keyboard is apparently mapped to the X button, although it doesn’t say so anywhere. This means I can’t allow the user to press X to cancel the password prompt, since that would make inputting any password with an 8 in it impossible. You’ll have to open the pause menu to go back. This was fixed in PICO-8 v0.1.12!

Thanks

That’s all for today. I still hope to add Polarium’s iconic electronica theme to the game, and maybe some sound effects, but then I’ll have to learn to compose music. Apart from that, this game is pretty much done. My first game! Ever!

PICO-8’s limitations are tiresome at times (although I never ran into real trouble, I just had to not store the levels in the dumbest possible way), but they really force you to focus. I’ve started some games before, but never finished them until now. Maybe I’ll make some more games now!

Comments