Motorola 6800 addressing modes

The MC6800’s addressing modes have a few things to be aware of.

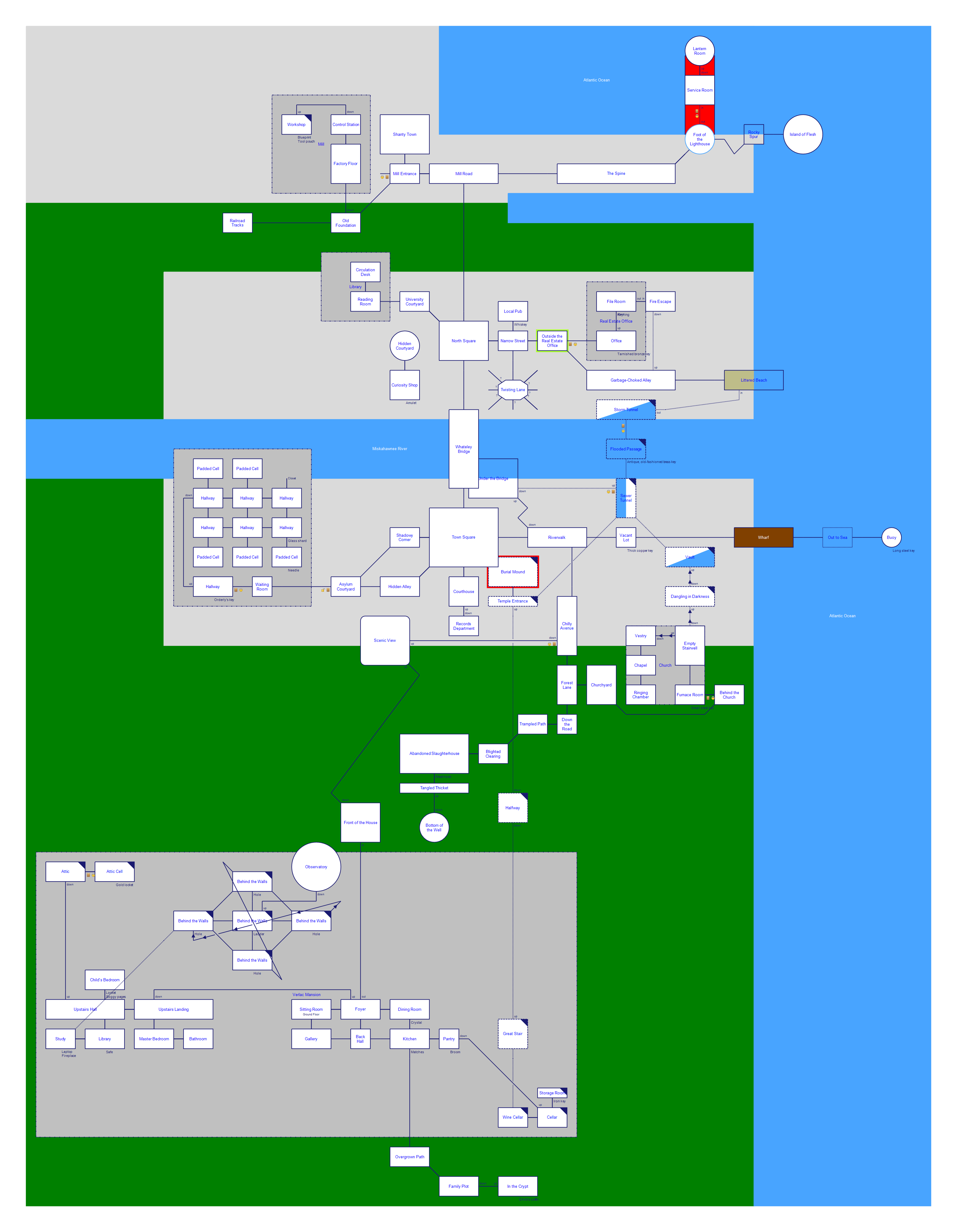

This post is part of a series on writing an emulator for the DREAM 6800 computer. Read the DREAM 6800 posts and look at the emulator’s repository.

The first step in emulating an M6800 system is to decode some instructions. The MC6800 MPU (CPU) uses 7 addressing modes to select operands, but with some added complications. All opcodes are 1 byte, and the opcode determines both the operation to take, and what operand to do it with; the addressing mode indicates the operand type.

I used the following resources to decode opcodes into operations and addressing modes:

- This nice MC6800 instruction table seems mostly correct (for some reason it claims

ABAuses the ACC addressing mode, but it’s obviously INH) - The official M6800 Programming Reference Manual is comprehensive (I found one probably mistake in the flags of one instruction, but I don’t remember which one)

Ostensibly, the MC6800 has seven different addressing modes. However, I realized almost immediately that some of the instructions treat some of the addressing modes a little differently. I decided to split these mode variants out into separate functions to handle them separately, so my emulator now actually has 12 addressing modes!

I’m not sure if that’s the nicest way to do this, but the way I structured my emulator meant I pretty much had to. To abstract as much as possible, and reduce code duplication, each opcode in my emulator is mapped to an optional accumualtor, an addressing mode function, and an instruction function. Th instruction function is as general as possible, like CMP(), which compares the contents of an accumulator with a value. The accumulator can be either A or B, and the value depends on the addressing mode, of course. The addressing mode function that returns the actual operand, and the instruction shouldn’t care whether that value came from memory or was an immediate value. So when an opcode doesn’t treat an addressing mode the way another one does, I create a new addressing mode function.

-

INH (“inherent”) just means that the opcode doesn’t require any operands; the operand is inherent to the instruction itself. An example of this is

NOP(no operation), orTAB(which always swaps the contents of accumulators A and B). These instructions are all just 1 byte, the opcode itself, and just exist as one opcode. -

REL (“relative”) is only used for branch instructions. There is one operand byte, and it’s treated as a signed 8-bit number.

-

ACC (“accumulator”) means that the operand is an accumulator register; the MC6800 has two 8-bit accumulators,

AandB. These instructions are also just 1 byte, but come as two opcodes, one for A and one for B (and usually also for other addressing modes). An example isNEG AandNEG B, which negates the contents of the accumulator.

Now, the first thing to notice is that instructions using any of the following addressing modes can also select an accumulator. Many of them come in pairs for A and B, like $84 which is the opcode for AND A, IMM (immediate value), and $C4 which is AND B, IMM. So ACC is really just a special case where the accumulator is the only variable, whereas the following modes select an accumulator and some other value. So at this point, decoding and executing an instruction basically looks like this in my emulator (pseudocode):

instruction, addressing_mode, accumulator = decode(opcode)

instruction(addressing_mode, accumulator)

The instruction AND might look like this:

function AND(addressing_mode, accumulator)

result = cpu.registers[accumulator] & addressing_mode()

-- Change flags in the status register based on the value of addressing_mode() and result

cpu.registers[accumulator] = result

end

Of note, addressing_mode is a function. It is in fact a closure that captured the value of the program counter at decode time, so I can call it as many times as I want and get the same operand. I can call it with an argument to set a value in memory based on the operand as well. OK, back to the remaining addressing modes.

-

IMM means the instruction will use a single operand byte as an immediate value. A couple of instructions, however, use two operand bytes as one immediate value. Not strange, since some registers (IX, SP, PC) are 16-bit, but it still means that you can’t rely solely on the addressing mode to fetch operands, you also need to consider the opcode. I solved this by inventing one new addressing mode, IMM16, which does exactly what it says on the tin: Take one immediate 16-bit value. Then I changed the opcodes that use IMM but expect two bytes to use IMM16 instead.

-

DIR means that the instruction takes a single byte, and uses it as an address in memory, where it finds the operand. Since it’s one byte, this means it can only be used for addresses $00–$FF, or the “zero page”. However, just like with IMM, there’s a 16-bit variant. It still uses only 1 byte to address the zero page, but instead of only addressing that single location, it addresses two consecutive bytes there. I called this DIR16.

-

EXT, or “extended”, caused a bit of headache for me. On the surface, it’s a 16-bit version of DIR that allows you to address the entire memory space; you take the following two operand bytes, treat it as a 16-bit address, and then use the byte at that address as the operand. However! Just like with IMM, some instructions are different: They take two bytes and treat them as an address, but they don’t look up the address in memory, they put it in a 16-bit register instead. Hang on, isn’t that what IMM16 does? It seems like it to me, so I just changed the opcodes that use EXT but as an immediate value instead of an indirect value to also use IMM16.

-

IDX, or “index”, is simple on the surface. It takes one byte as its operand, and then adds the 16-bit index register IX to it in order to form an address that the instruction can use. Use for what? Therein lies the rub. Some instructions need to read or store a 16-bit number in this location, so they do the same thing as “DIR16” – they add the operand and the index register, and then read/store two consecutive bytes at that location. And some instructions don’t use this address to access memory at all; they add index and operand and treat the result as a semi-immediate 16-bit value.

So there you have it: The MC6800’s addressing modes, and all the gotchas they surprised me with while I tried to execute them. Now I should be able to execute some DREAM 6800 programs, hopefully!

Comments